Key points

- All systems need failure testing

- Apache Kafka’s architecture is resilient, but in the wider context of your system it might not be

- You need to understand a bit about Kafka internals to know how it could fail

| (Note: This post assumes you know the fundamental concepts of Kafka – if you need a primer/refresher, check out this Apache Kafka intro.) |

Why failure test Kafka?

Maybe this is what you’re asking yourself – after all, Apache Kafka is well known for being resilient. And since, as highlighted on the Apache Kafka website, it’s used by 80% of Fortune 500 companies, surely it’s so tried and tested that it must be bulletproof by now?

Well it’s not so much Kafka itself that we need to test. As anyone who’s implemented it will know, it’s not the simplest of technologies to configure, especially if your use case or requirements are slightly out of the ordinary. Also, it might be that you’re using a COTS product which wraps Kafka, and has different resilience characteristics and behaviour.

But, most importantly, if you’re running Kafka it doesn’t exist in a vacuum: You’ve implemented a wider system of producers and consumers, and other upstream and downstream components, and it’s this system you need to test.

Just like all other kinds of testing, we can’t just assume that the system will behave how we want when it fails. It’s essential to carry out failure testing so that:

- We can be confident that the system does what we expect when something goes wrong (which it will)

- We learn the nuances and edge cases in a controlled way, rather than on a call-out at 2am with live data at stake, limited time, and a considerable amount of stress!

- We can document the above so that future teams can understand the behaviour and limitations of the system, and we can have runbooks for any manual recovery scenarios.

So let’s dive in.

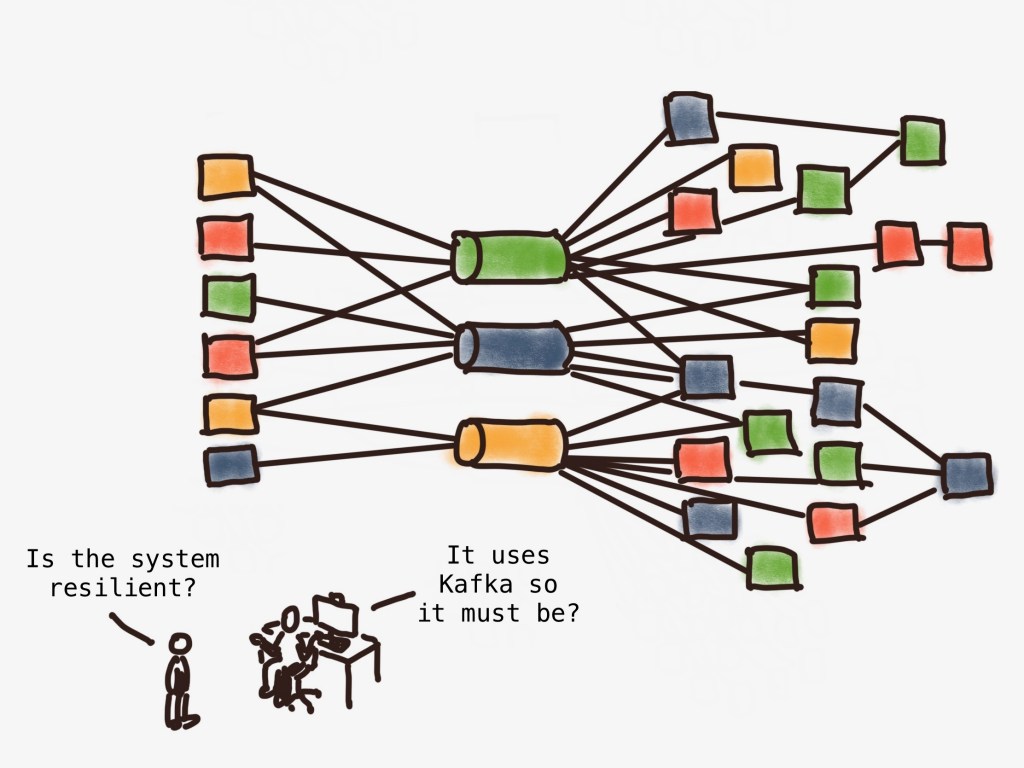

The system architecture

On a client engagement recently, we were building a system which looked like this:

To avoid rejecting messages at the front door, we needed to ensure as far as possible that we could reliably persist messages as they arrived, even if we suffered an infrastructure failure. But even more important was that having accepted a message, we could be confident that it had indeed been durably persisted.

In other words, we wished to optimise for durability, and resilience – in that order.

In practice, this meant:

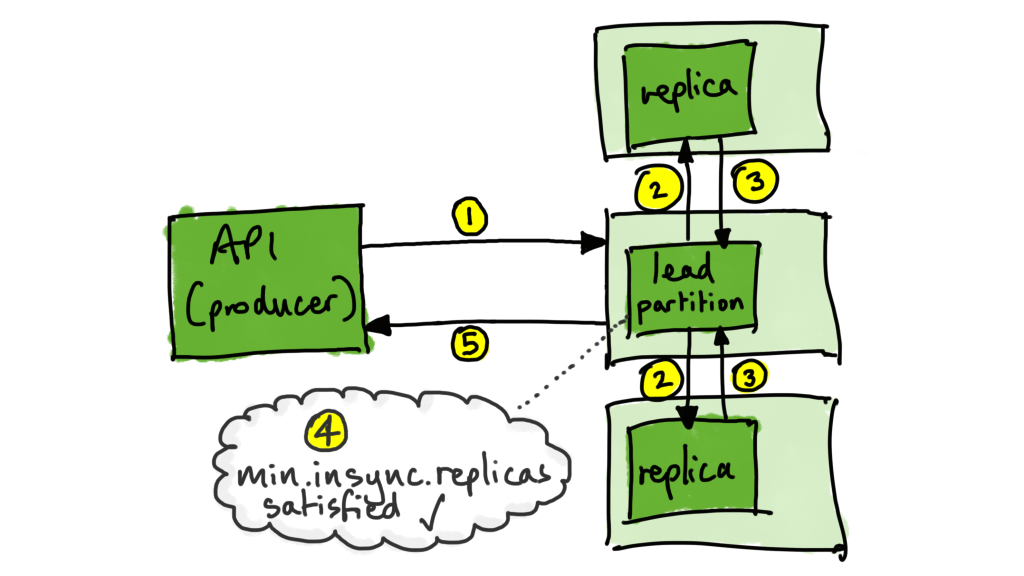

- having 3 brokers in the cluster (there was no need for more as our throughput was very modest)

- configuring a

replication factor of 3for the topic (in other words, data should be written not just to the partition leader, but also to two other replicas on different brokers). - to set

acks=allfor the producer (which in our case is the front door web service API). This means that the producer only wants a successful acknowledgement if all the available in-sync replicas have persisted the message. - to set

min.insync.replicas=2for the topic. This ensures that the message has been durably persisted on at least two in-sync replicas of the partition before responding with a successful acknowledgement back to the producer.

The upshot of the above configuration is that:

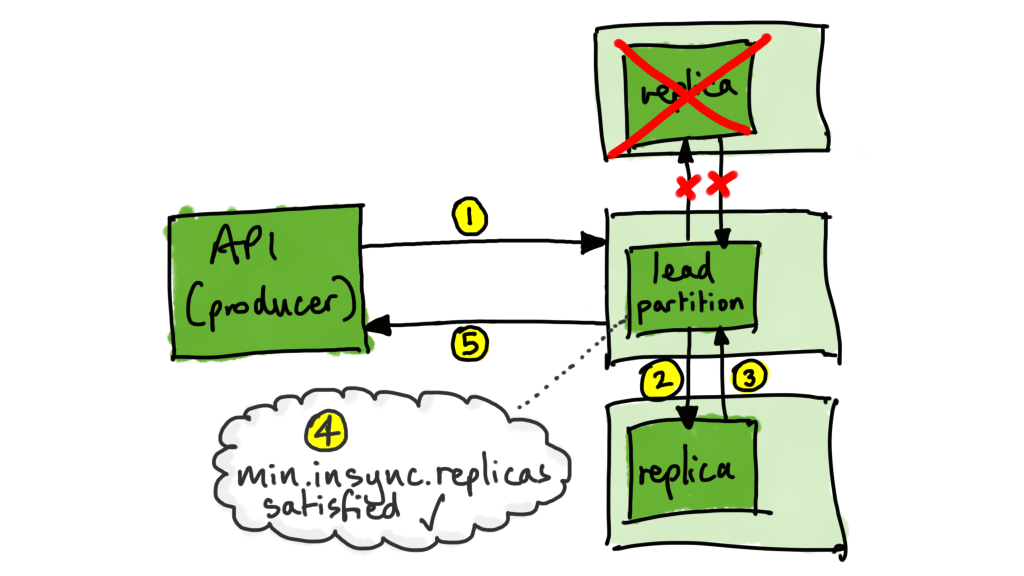

1. We could tolerate the loss of one broker and still accept and store messages

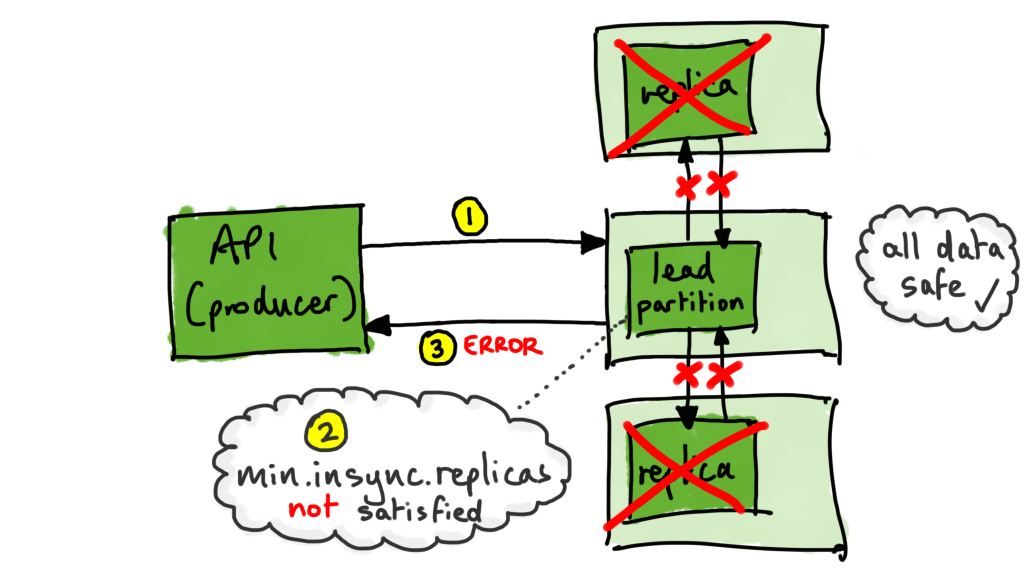

2. We could tolerate the loss of two brokers and still have all our data safe

but…

3. We could not accept new messages with two brokers unavailable, because we wanted to make sure we had at least two copies safely stored. (The producer will receive a NOT_ENOUGH_REPLICAS error).

The failure scenarios

To identify the failure scenarios to target for any system, we need to understand the internal architecture of the system under test. Which meant, in this case, that we needed to know enough about how Kafka works to figure out the things that could go wrong. In particular, we focused on some of the different key roles that Kafka brokers can play:

Active Controller

One broker in the cluster will be assigned the role of Active Controller. Its main role is to manage the partition replicas and to promote leaders in the case of failure.

If the Active Controller becomes unavailable, a new one is elected using a consensus service (Zookeeper or KRaft depending on your version).

Partition Leader

Each partition of a topic will have a broker assigned to be the leader of that partition. The Partition Leader handles all the reads and writes to that partition, and keeps track of which replicas of the partition are in-sync.

If that broker becomes unavailable, the Controller works to elect a new one from the available in-sync replicas.

Group Coordinator

Each consumer group has a broker allocated as its coordinator, which is responsible for allocating partitions, and keeping track of the consumers in the group. The internal topic __consumer_offsets stores the committed offsets for each group. The leader of the partition that stores that group’s offsets is the Group Coordinator for that consumer group.

Brokers can, and will, have more than one role, especially when you consider that every partition needs a Partition Leader. However, for the purposes of this post, we’ll assume that we have only one partition, to keep things more concise. Also, we’ll consider only one consumer group. So, depending on the roles that failing brokers have, our first-cut failure scenarios looked like the following:

| Scenario | Expected outcome |

| One broker unavailable: no role | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Active Controller | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Partition Leader | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Group Coordinator | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Active Controller and Partition Leader | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Active Controller and Group Coordinator | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Partition Leader and Group Coordinator | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| One broker unavailable: Active Controller, Partition Leader, and Group Coordinator | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable: no roles | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Active Controller | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Partition Leader | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Group Coordinator | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Active Controller and Partition Leader | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Active Controller and Group Coordinator | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Partition Leader and Group Coordinator | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable, whose roles include Active Controller, Partition Leader and Group Coordinator | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| All three brokers unavailable | Producer can no longer write. Consumer can no longer write. Potential data loss. |

Note that we haven’t talked about unavailability of Zookeeper. I’ve deliberately missed that out for two reasons:

- It increases the number of failure scenarios to consider, and I want to focus on just the key concepts in this post

- If you’re using KRaft (officially available with Kafka 3.3.1 onwards) then Zookeeper will obviously be irrelevant

Identifying roles

In order to target the right broker(s) for each test, we needed to know which roles brokers had. Unless you’re using a product which provides a UI for your cluster, you’ll find the following commands useful:

Find the controller

With Zookeeper:

./kafka/bin/zookeeper-shell.sh [comma separated list of zookeeper_host:port] get /controller

With KRaft:

./kafka/bin/kafka-metadata-quorum.sh --bootstrap-server [comma separated list of broker_host:port] describe --status

Find the partition leader

./kafka/bin/kafka-topics.sh --bootstrap-server [comma separated list of broker_host:port] --describe --topic [topic name]

Find the consumer group coordinator

Note that at least one consumer in the group must be running for this to work:

./kafka/bin/kafka-consumer-groups.sh --bootstrap-server [comma separated list of broker_host:port] --describe --state --group [consumer group name] --all-topics

How to make things fail

In the table above, I’ve written “unavailable”, but what does that mean? There are a number of ways this could happen. Here are some examples, together with (manual) ways of simulating them:

Process failure

Simulating the failure of a Kafka process is simple to achieve manually by killing the relevant process.

ps -ef | grep kafka

sudo kill -9 <process ID>

You will of course need to know how to restart the process ready for the next test!

Network partition

To simulate a network failure rendering brokers unavailable, there are different options depending on where you’re hosting Kafka.

On Linux you can use iptables to block the ports used by Kafka:

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 9092 -j DROP

iptables -A OUTPUT -p tcp --dport 9092 -j DROP

The default port for connections in and out of Kafka is 9092, or 9093 for TLS. Your setup might differ, so check server.properties, and also check the advertised.listeners property which defines the address and port which clients use to connect.

On Docker, you can disconnect all network traffic:

docker network disconnect <network name> <container name>

On AWS EC2, you can use security groups by assigning to your instance an empty security group (containing no rules) for both inbound and outbound. However, here are some points to bear in mind:

- Security Groups are stateful, so if an inbound connection is allowed, the outbound response will be allowed even if there are no rules to allow it. This is why you need to set both inbound and outbound rules.

- Changing a security group will not terminate any current connections if they are tracked. So before simulating the failure, make sure that your instances are running with permissive untracked connections. See the AWS docs on this. I suggest creating a security group with a permissive

0.0.0.0/0rule for this purpose – but of course this is only to be used if it’s secure to do so; clearly you would never use this in a Production VPC / account. - Be aware that access can be granted to instances associated with a specific security group. In other words, security groups can refer to other security groups. This is important to remember when changing the security groups of your Kafka nodes for the purposes of failure testing, because you might unwittingly deny access to, say, an observability service you were using to record results of the testing!

Availability Zone outage

If you’re running in the cloud, you should consider and test what would happen if an AZ failed. This can be very difficult to simulate with the techniques above, but if you’re using AWS, you can achieve this with Fault Injection Simulator.

Expected outcomes

In the right hand column of the table above, I’ve indicated the results we were expecting from each scenario based on our configuration. I’ll summarise it here:

| Type of scenario | Expected outcome |

| One broker unavailable | Producer continues to work. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Two brokers unavailable | Producer can no longer write. Consumer continues to work. No data loss. |

| Three brokers unavailable | Producer can no longer write. Consumer can no longer write. Potential data loss. |

However, this is only looking at the Kafka cluster and its immediate clients. The expected outcomes need to consider the wider system – for example, what are the implications of the producer being unable to write? How does our system respond to this?

Even in the “one broker unavailable” scenarios, the cluster will take time to detect that something is unavailable, and then there will be a period of time while leadership elections take place for any partition leaders that were lost, during which no writes or reads can take place to those partitions. Even worse: If the failure took down the Active Controller, a new one will need to be elected before the partition leaders can be elected. So in other words, although the “system continues work” as I wrote above, there is a period of time where things don’t work, which will be in the order of seconds not milliseconds!

If we go back to the system architecture I showed earlier, we can see that now we have to consider what our timeouts and retries should be.

[Diagram showing API client failing to deliver messages while Kafka is recovering]

In my client’s case, we wanted to avoid the scenario where messages could not be delivered to the API since replaying them was non-trivial, so we tuned our retries and timeouts to accommodate the recovery time we saw from the Kafka cluster. Our failure testing informed these decisions.

Conclusion

This post has focused on failure testing of systems which use Kafka, but it’s important to note that all systems should be failure tested before they go live, and on an ongoing basis. The more change your system has, the more frequently you should be carrying out failure testing. If your architecture and processes allow it, you should consider chaos engineering, but this is still a way off for most organisations realistically.

Although the concepts and techniques I’ve presented above are basic, it’s hopefully highlighted the types of considerations and techniques which can be used to target different failure scenarios for Kafka-based systems. Even if you don’t test every scenario, at least make sure you understand the behaviour of your wider system when Kafka suffers problems.

You need to understand something about how Kafka works behind the scenes to know how to hit it hard. Gracefully shutting down a non-essential broker won’t tell you much – take down its Active Controller and Partition Leader and see if your system does what you expect. Remember that the real world plays dirty. And if you haven’t prepared for the worst, then the worst will happen!

Leave a comment